St Werburgh's Catholic Parish, Chester

Catholicism in Chester

Chapter I: Penal Times

Distribution of Catholics in Chester in 1767. Distribution of Catholics in Chester in 1767. |

The Eighteenth Century

Fears of a Jacobite Rising, first in 1715 in favour of the Old Pretender and later in 1745 in support of Charles Edward, Bonnie Prince Charlie, tended to bring harassment to the Catholic population, among whom were Stuart supporters. As we have already seen, the Catholic gentry in the Wirral suffered imprisonment after the '15 Rising. In 1716, Catholics were obliged to go through the annoying and costly business of registering their estates with the Clerk of the Peace of the county in Quarter Sessions. The information which was then obtained could also prove useful to Parliament in drawing up a land tax, "for granting an aid to His Majesty by laying a tax upon Papists". It was only the lack of an efficient Civil Service which prevented Catholics from feeling the full weight of this legislation.

As far as we can tell, the career of only one Catholic in Chester was affected by the advent of Bonnie Prince Charlie; and he at the time of the Rising was not a Catholic. This was Charles Corn, the son of James Corn who came originally from Betley, Co. Stafford, but was in Chester at the time of his son's birth in 1716. Charles's mother was Elizabeth, the daughter of Charles Butler of Great Eccleston in the Fylde, whose family suffered greatly for their loyalty to the Stuarts in the '15. When he grew to manhood, Charles himself became a distiller in Chester. Bonnie Prince Charlie's landing in Scotland was the signal for him to take up arms and join his forces. After the defeat of Culloden he fled to Ireland, and there became a Catholic. Before long, he went to Louvain where he declared his intention of becoming a priest. His age - by then he was thirty - and his ignorance of Latin prevented him from being accepted at the College of Douai. He was, however, eventually received at St. Gregory's College in Paris, through the influence of Cardinal Stuart and of John Towneley of Towneley Hall, Burnley, who had been tutor to the Chevalier de St. George, James Francis Edward Stuart. John Towneley paid his fees of £600 a year, and supplied him with clothing. Ordained in 1756, he was very soon appointed confessor to the English community of the Immaculate Conception, or the Blue Nuns as they were called, in Paris, a position he retained until his death in 1777. His sister came as a lady boarder to the convent in 1767, and together they became generous benefactors of the Blue Nuns. In his will, Father Corn left the nuns a yearly annuity of £185 in shares in India and an annual rent of £432. He was buried in the convent chapel, before the high altar. Father Corn, therefore, never returned to work as a priest in his native town, but was called on, instead, to share the exile of English nuns abroad, to whom he gave great edification by the holiness of his life.25

Meanwhile in Chester, the survival of a number of documents enables us to build up a clear picture of the Catholic community there in the eighteenth century. On the turn of the century, in 1705 and 1706, "Accounts of Papists and Reputed Papists residing in the City of Chester"26 were drawn up by the Justices of the Peace in Quarter Sessions. These give their names, station in life, dwelling place, and if they had any, the value of their estates. An analysis of the list for 1706, which is slightly fuller than the one for the previous year, shows one hundred and four Catholics. This is an increase of eighty three since 1688, possibly to be accounted for by the inclusion of wives and children. Because it was a list drawn up by the J.P.'s it arranges the Catholics in the Wards of the city, not in the parishes, as the Ecclesiastical records do. Eight Wards are mentioned with Catholics living in them, as follows:

| St. Giles | Northgate | St. John's | St. Olave's | Eastgate |

| 28 | 23 | 19 | 10 | 8 |

| St. Thomas | Trinity | St. Michael | ||

| 8 | 3 | 1 |

The most prominent Papists are still the Wirral gentry, although strictly speaking, some did not live in Chester, unless they had a town house there. Sir James Poole is placed in St. Martin's Ward, with an estate valued at £300 a year. William Fitzherbert, in the Northgate Ward, has estates assessed at £500 a year, and Richard Braithwait, Esquire, in St. John's Ward, is worth £200 a year. Two years earlier, William Fitzherbert's two horses and arms, including his sword, had been seized by order of Edward Partington, the Mayor. The two horses and swords owned by Richard Braithwait had not been taken, "because neither of them is worth £5", the sum fixed by the penal law.

William Fitzherbert came from the distinguished Derbyshire family who gave a Martyr to the Church in the person of Thomas Fitzherbert. The family estates lay in Swynnerton in Derbyshire. William never lived there, but on the death of his father, Basil, allowed his eldest son to take over the property there. He himself continued to live in a house in Northgate Street, which he either owned or rented. A map of Chester, drawn by Alexander Lavaux in 1745, shows it lying on the west side of the street, between Princess Street and King Street, and marked as "Mr. Massey's house". Richard Massey was William's grandson, and as such appears on the list of recusants with the other members of the Fitzherbert family. As a child, he lived with his grandparents in Northgate Street after his parents, Jane Fitzherbert, William's eldest daughter, and Richard Massey of Rixton, County Lancs, had died.

Katherine Wright, the wife of John Wright of Brewer's Hall also appears on the list, but for some reason not John himself, although in 1717, he was registering his estates as a Papist.27 Possibly in the intervening years, he had become a Catholic. Ann Crompton is also named. She was the wife of Richard Crompton, Esquire, of St. Martin's Ward, who is described in the list drawn up in 1705 as "a gentleman of very considerable substance".

The families and servants of these members of the gentry number in all twenty nine, i.e., they represent nearly 28%, or slightly more than a quarter, of the total number of Papists listed, showing how important the gentry were to Catholicism in Chester.

Because the Penal Laws still remained on the Statute Book, the professions were still virtually closed to Catholics. There were, however, at least two Catholic teachers in Chester in 1706, William Kingsley, a teacher of Mathematics, and Bartholomew Casey, a fencing master. Both, presumably, were attached to one or other of the different "Academies" which flourished in eighteenth century Chester. The trades and crafts of the growing city gave easier opportunities of a livelihood to the Catholics. In the clothing and textile trades, there were two weavers, one of them, Richard Arnett, probably the son of the miller, William Arnett, who appeared on the 1678 list, a tailor, and a woman engaged in bone lace-weaving. There were also a periwig maker, a tanner, a miller and a ginger bread maker. Among the poorer craftsmen were a cobbler, a carpenter (a journeyman, not a master), and three labourers whose work is not specified. Four invalid soldiers, belonging to Chelsea Hospital, are also listed, and they presumably, were elderly men.

Some sixty years later, in 1767, the Government ordered the vicar of every Anglican parish to draw up a list of all the Papists in his parish, giving their names, ages, occupations, and the number of years they had resided in the parish.28 How far, again, this Papists' Return, as it is called, is complete, it is impossible to say, but it enables us to compare the Catholic community of Chester in 1767 with what it was like in 1706, and its details give us an even fuller picture than before.

The Catholics now number one hundred and twenty nine, an increase of twenty five. This is not a dramatic increase, and its implications will be discussed later. They are distributed among the parishes in the following way:

| St.Oswald's | St. John's | St. Mary's | St. Peter's | St. Martin's |

| 46 | 43 | 13 | 9 | 9 |

| St. Bridget's | St. Olave's | St. Michael's | Holy Trinity | Cathedral |

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The most striking difference between the composition of the community of 1706 and that of 1767 is the complete absence of the Wirral gentry. This does not mean that they had died out, or had conformed. The vicar of Eastham reported in 1778 that the household of Sir William Stanley, who was abroad and under age in 1767, had increased the number of papists in his parish from forty nine to sixty one. Rather, it would seem to indicate that the Catholic population of Chester, though it might still remain an inward-looking community for many years yet to come, was now, at last, numerous and strong enough to stand on its own. The Catholic Relief Act of 1778 had still to be passed, but so long as Catholics remained inconspicuous, they were left alone.

It is quite true that Incumbents of the parishes were still receiving from the Bishop of Chester, as late as 1825 "Articles of Enquiry preparatory to Visitation".29 This was a detailed questionnaire concerned with various aspects of parochial life. One section dealt with "Popery" in the parish. The incumbent had to say:

1) How many papists he had in his parish and what was their rank;

2) Whether anyone had been lately perverted to popery, and by whom;

3) Whether there was any place in the parish in which papists assembled for worship, and where it was situated;

4) Whether a popish priest resided in the parish, or resorted to it;

5) Whether there was any popish school kept in the parish;

6) Whether there had been any Confirmation or Visitation made by any popish bishop in the parish.

The wording of the questions has an unpleasant ring, but the answers are normally free from any invective. Only once did a vicar remark, "There is not a papist in the parish that I can hear of after strictest enquiry; consequently no popish bishop ever molests it". Moreover, the numbers given, we know from other sources, are incomplete.

By 1767 a wider range of occupations was open to Catholics, as they became more easily accepted in the city. There were two Catholic surgeons, named Bernard and Alexander Racketta or Raquet, probably a father and son, though they were not Cestrians by birth and had not been resident for long. There was also a Catholic merchant, Francis O'Brien, who had been living in Holy Trinity parish for the last seven or eight years, and whose wife and children were Protestants.

During the eighteenth century and even later, Chester avoided any kind of industrialisation. It preferred to be a residential and cultural city, dependent for its revenue on the numerous trades and crafts which made it the market for north west Cheshire and North Wales. Its only large industry, as the number of tan-yards showed, was in leather and allied crafts. Here the largest number of Catholics found a means of livelihood. Eight were cordwainers or shoemakers, seven belonged to the very old craft of glover, one was a skinner and another a tanner. The clothing and textile trades, as in earlier times, also attracted Catholics. There were four tailors, two weavers, a breeches maker, and a dealer in worsted. Among the craftsmen were two cabinet makers and an upholsterer, as well as a carpenter, a sawyer, a cooper and a paper maker. William Briscoe, who had been living in Chester for forty years, was a barber established enough to employ an apprentice of fifteen, who was also a Catholic. Domestic service absorbed eight Catholics, but none of them in the homes of the Catholic gentry. Apart from the tradesmen, the largest number of Catholics, as the table shows, were labourers. Apart from the pavior, nothing indicates the nature of their work, but it might have been road-making or repairing. The map shows that the majority of them lived on the outskirts of the city, beyond Northgate and Foregate Street, foreshadowing where the future Catholic parish was to lie. Moreover they must have been among the poorer element of the population, as they were to be in the nineteenth century, and as the Anglican vicars so often remark, whereas the more central parishes, like St. Peter's which covered the main shopping area of Eastgate and Watergate Streets housed the glovers, the tailors and the surgeon. One can see the pattern of the future already being laid down. (See table below: "Places of Residence and Occupations 1767.")

| Places of residence and occupations 1767 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANGLICAN PARISH | PROFESSIONS | LEATHER INDUSTRY | TRADES | |||||||||||||

| Surgeons | Merchants | Cordwainers Shoemakers |

Glovers | Skinners | Tanners | Tailors | Weavers | Breeches Makers |

Dealers in Worsted |

Travelling Spinners |

Barbers | Bakers | Chimney Sweeps |

|||

| St. Oswald's | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| St. John's | Priest | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| St. Mary's | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| St. Peter's | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| St. Martin's | ||||||||||||||||

| St. Bridget's | ||||||||||||||||

| St. Olave's | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| St. Michael's | ||||||||||||||||

| Holy Trinity | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Cathedral | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 17 | 14 | ||||||||||||||

| NO. OF PERSONS |

CRAFTS | DOMESTIC SERVICE | LABOURING | |||||||||||||

| Cabinet Makers |

Carpenters | Upholsterers | Sawyers | Coopers | Paper Makers |

Gardeners | Male Servants |

Housekeepers | Female Servants |

Husbandmen | Fishermen | Labourers | Paviers | |||

| St. Oswald's | 46 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||||

| St. John's | 43 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | |||||||||||

| St. Mary's | 13 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| St. Peter's | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| St. Martin's | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| St. Bridget's | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| St. Olave's | 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| St. Michael's | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Holy Trinity | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Cathedral | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| TOTAL | 129 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 14 | |||||||||||

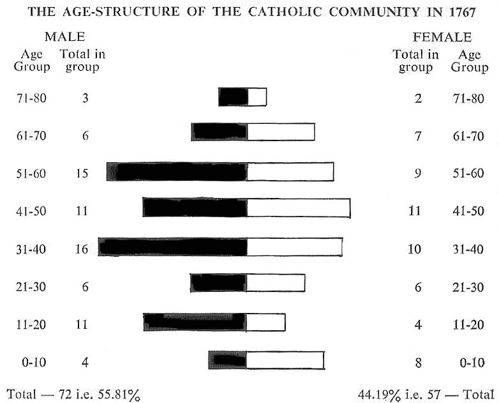

A more detailed analysis of the Papists' Returns can be made to throw light on two other important factors connected with the growth of Catholicism at this period. These factors are the age-structure of the Catholic community, and the pattern of immigration of Catholics into the city.

The "pyramid graph" below shows at a glance what the age-structure was like.

There are several important points to be noticed about this graph. Its uneven shape will be immediately apparent. In addition, it shows that the male Catholics outnumbered the female by as much as 11.62%. Moreover, it was an ageing community. Men and women over fifty years of age made up nearly one third - 32.55% - of the total, whereas children under the age of ten represented only 9.3%, four only of them boys. This latter fact may well reflect the heavy infant mortality of the time. In the child-bearing age group, the twenties to the fifties, unmarried men were twice as numerous as married ones, 70% as against 30%. Among the latter group was a widower of thirty seven, left with four young children, all under ten, and another man, probably a widower, aged thirty one, with a child of two and another of nine months, a sign of the dangers of child-bearing for the eighteenth century woman. Married women in this age-group (60%) outnumbered unmarried ones (40%) by 20%. Finally, it will be noticed how small were the age-groups 11 to 20 and 21 to 30, i.e. the marriageable ages. All in all, it can be said that the Catholic community in 1767 was in an unhealthy state. Its growth could, at best, be slow and precarious. Indeed, if it had continued like this, it might have died out altogether. It was only the immigration of Catholics into the city, the injection of new blood into the Catholic body, which saved the situation.

As far as we can tell, only three families, named Keay, Williams and Wareing, survived the vicissitudes of the first half of the eighteenth century, and remained true to their faith. The oldest was the Keay family. William Keay, who was a cordwainer or cobbler living in St. Oswald's parish, was born in 1696. He was summoned in 1721, to appear before the J.P.'s of the city, together with five other "Papists, dangerous and disaffected to His Majesty and his Government" - though there is nothing to show it. He was ordered to take the oath prescribed by the Test Act, but refused to do so. He was still alive in 1767, at the age of seventy one, and had a son, also a Papist, who was then aged thirty five, and a cobbler like his father. One of William Keay's companions in 1721 was a "husbandman" named Thomas Williams, who was already known as a Papist in 1706. He also lived in St. Oswald's parish, and was probably a farm labourer, rather than an owner of land. His son and grandchildren were all Catholics in 1767. The third family was the Wareings. Peter Wareing, a gardener, with his wife and five children, were alive in 1706. A John Wareing, either a brother or a son, and described as a glover, came before the J.P.'s in 1721 and refused to take the oath. One of Peter's sons, a gardener like his father, was living in St. John's Parish in 1767 and was a Catholic. There were, therefore, as far as we can tell, only six Catholics left in 1767 who could call themselves real Cestrians. They represented just under 5% of the total Catholic population. The remainder were all immigrants into Chester.

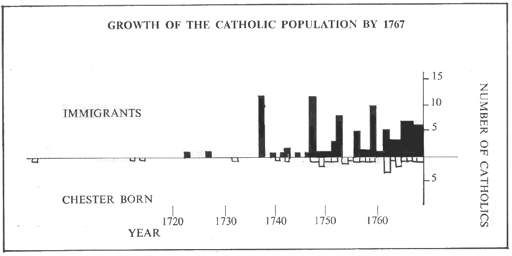

In addition to telling us the ages of the Catholics they list, the Papists' Returns of 1767 also say how long they have been resident in the city. This enables us to see not only the rate, but also the pattern of growth of the Catholic population. The following diagram illustrates this. It at once makes apparent how vital immigration was to the survival of the Catholic body in Chester.

It is clear from this diagram that Catholics moving into Chester outnumbered those born there by nearly four to one, while the parents of several born there were not themselves Chester born. Judging by their surnames, some of the newcomers into the city were of Welsh extraction; for instance, a family named Davies who by 1767 had been living there thirty years, a gardener named John Jones and his wife, Anne, and a young paper-maker named Luke Lloyd and Dorothy, his wife.

The greater number, however, have Irish names, and except for the merchant, Francis O'Brien, they were among the poorer labourers in the city. This is borne out ten years later, by the enquiry made by the Bishop of Chester, preparatory to his Visitation of his diocese. In answer to the question, "Are there any Papists in your parish, how many, and of what rank?" the Vicar of St. John's replied, "the few Papists we have are all of the lower class of people". Similarly, those in St. Martin's are described as "very poor people", and the Vicar of St. Olave's gave the information that "sometimes the lodging houses receive by accident an Irish labourer of the Popish sect". Only in St. Mary's parish were there said to be "six Papists of a middling station of life". Thus, we can already discern, years before the Famine of the 1840's, the beginnings of the Irish settlement, which was to play so important a role in the future St. Werburgh's parish.

Some of the people moving into Chester came as family units, made up of husband, wife and one or more children, but they were outnumbered by single men, presumably coming to find work, often as "labourers". Until about 1760, moreover, they came in "waves" rather than in a steady flow. This is particularly true of the years 1738 and 1748, as the diagram shows.

Finally, and most important of all, by 1767 Chester at last had a resident secular priest, Father John Cooling. During the seventeenth and early eighteenth century, as has already been seen, the Catholics of the city relied, for their spiritual needs, on Jesuits who were acting as chaplains to the Catholic gentry of the area. This practice continued well into the eighteenth century, when a Father Michael Tichburn and later a Father James Farrar30 were both chaplains to the Stanleys of Hooton, who had a private chapel in their Hall. A Benedictine, Dom Lewis Laurence Fenwick, stationed at Woolston Hall, the home of the Standish family near Warrington, visited Chester at least, for he died here in 1746.31

Between 1741 and 1747 the names of several secular priests have survived, James Meston, Thomas Lydell, Tindall and Richardson,32 and in 1750 the Obituary Notices of the Secular Clergy record the death in Chester of "Mr. Preston".33

Father John Cooling, or Cowling as he is also called, is the first secular priest about whom we have some details.34 He was born in 1711, either at Wrightington or Wigan, and was educated for the priesthood at the English College in Rome. After his ordination, he spent the first part of his priestly life serving the Catholic Chapel at Singleton, in Poulton in the Fylde. A mob attacked the chapel in 1746, crying "No Popery", and for a time he had to carry on his missionary work in private houses. He was transferred to Chester in 1758, and remained there until his death ten years later. The Papists' Returns for 1767 describe him as "a gentleman", living in the parish of St. John's, with his housekeeper, Ann Abram. As they are both stated to have been resident for nine years, it is possible that she had accompanied him from Lancashire when he moved to Chester.

Father Cooling was succeeded in 1770 by Father John Kitchen.35 With Father Kitchen, there began that long line of missioners, trained in Douai and later in Ushaw, who built up, by their apostolic zeal and pastoral care, the nineteenth century Church in Chester. Like Father Cooling, he was a Lancashire man, born into an old recusant family from Stone Bridge, in Barton near Preston. He went to Douai at the age of fifteen, and on the completion of his studies, was ordained in 1768. The next two years were spent in teaching in the College, until on May 15th, 1770, he was sent on the English Mission. He seems to have come immediately to Chester, where he was usually known under the name of Marsden.

Though he may not have opened it, it is under Father Kitchen that we hear for the first time of a Catholic Chapel, a sure sign that the Catholic population was beginning to expand. It was situated, in the words of the earliest Directory for Chester, compiled in 1789, "in the part of Foregate Street, opposite Love Lane, under which is a house where the priest of that (Romish) persuasion usually resides". Writing a hundred years later, Mgr. E. Slaughter described it as "a room over Mr. Parry's coach-house, close to Parry's Entry", though some older inhabitants had told him "it was in the Entry itself".36 The site of the house and Parry's Entry have long since been demolished, to make room for modern shops, but it was here that Mass was said openly again, and the Sacraments administered to the hundred or so Catholics who made up the congregation. The choice of Parry's Entry for the Chapel is not without significance. It lay outside the city walls, in an inconspicuous place, and in an area where the Catholics were most numerous. Possible also, Mr. Parry was a Catholic.

By 1774, Bishop William Walton, the Vicar Apostolic of the Northern District came, and confirmed sixty three people, though some may have come from Cheshire. In October, 1793, when Father Kitchen died, the Catholic community in Chester could look forward with more confident hope towards the emancipation which lay ahead.

| Jesuits in Chester | Contents | CHAPTER II: The Priests of the Nineteenth Century |

From Catholicism in Chester: A Double Centenary 1875-1975 |

||

| © 1975 Sister Mary Winefride Sturman, OSU | ||