St Werburgh's Roman Catholic Parish, Chester

Catholicism in Chester

Chapter III: Growth in the Nineteenth Century

Interior of the Chapel of St. Werburgh, Queen Street, with Daniel O'Connell lying in state, 1854. Interior of the Chapel of St. Werburgh, Queen Street, with Daniel O'Connell lying in state, 1854. |

We have already seen that in 1767, when the total population of Chester was over 14,000, the Catholics numbered only one hundred and twenty nine. It was also suggested that the Catholic body was an ageing one, which could grow only very slowly, unless immigrants came to swell Its ranks. This picture is borne out by the next set of figures sent to the House of Lords by the Bishop of Chester in 1780. There, he reported that they numbered forty six, distributed in the following Anglican parishes:

| St. John's | St. Mary's | St. Peter's | St. Martin's |

| 23 | 12 | 5 | 2 |

| St. Olave's | Trinity | ||

| 2 | 2 |

These figures may be incomplete. Nevertheless, during the thirteen years which had elapsed since the last Returns, many of the older people would have died, leaving behind a much smaller number of young people to fill the gaps. It seems true to say that, even if the drop in numbers was not as severe as it appears here, it does give an indication of what was happening. The 1770's may well have been the lowest ebb of Catholicism in Chester before the turn of the tide.

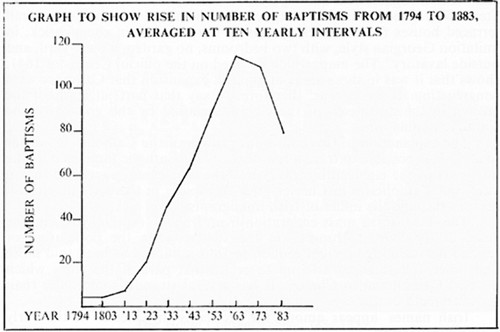

After 1780, however, we can begin to make use of the surviving registers of the Mission. The baptismal registers run continuously from 1794 down to the present day. The marriage registers are almost as complete, starting from 1823. Unfortunately, there is a gap of twenty five years in the burial registers from 1836 to 1861, and they are incomplete for the beginning of the century. It is the baptismal registers which are particularly revealing. By averaging the number of baptisms at ten-yearly intervals, and plotting the figures on a graph, it is possible to see how rapidly the number of baptisms rose during the nineteenth century. Beginning with an average of four baptisms a year between the years 1794 and 1813, it reached one hundred and fifteen a year between 1854 and 1863. After that, though one hundred and twenty nine were baptised in 1863 - the same figure incidentally, as there were Catholics in Chester a hundred years before - the numbers began slowly to fall. This was caused partly by the slackening off of immigration, and partly by the development of St. Francis's parish. The highest percentage increase took place at the beginning of the century, especially between the years 1814 and 1823, when there was a 185% increase. After the 1830's, though there was a steady increase it remained at about 33%. The baptism figures therefore show that there was a rapid growth in the numbers of Catholics in Chester in the first half of the nineteenth century, and especially between 1814 and 1823.

Continuity of the baptism registers also makes it possible to use a conventional and recognised method of estimating the size of the Catholic population, though the resultant figures show a trend rather than make any claim to absolute accuracy. By taking the average number of baptisms at ten-yearly intervals and multiplying by thirty, the following table can be drawn up to show the approximate size of the Catholic population between 1794 and 1883. The date given represents January 1st of every sixth year in the ten-yearly groups:Â

| Year | 1799 | 1809 | 1819 | 1829 | 1839 | 1849 | 1859 | 1869 | 1879 |

| No. of Catholics | 120 | 210 | 600 | 1,440 | 1,891 | 2,580 | 3,450 | 3,330 | 2,400 |

| % Increase | 75% | 186% | 140% | 31.2% | 36.5% | 33.7% |

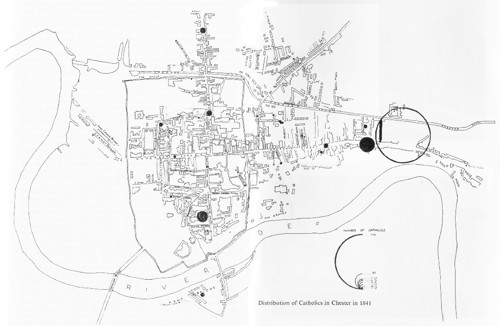

These figures seem surprisingly high and they have to be accepted cautiously. At the same time, they fit in with the general rise of the population of Chester itself, and of the parish of St. John's in particular. Between 1801 and 1831, the total population of the city rose from 14,860 to 21,344, i.e. by 43.6%. The two Anglican parishes affected by this growth were St. Oswald's and St. John's, which had well over half the total population of the city between them, with St. John's taking the greater share. This expansion continued from 1832 till 1861, St. John's rising from 6,035 in 1835 to 9,835 in 1861. By far the greatest area of expansion therefore took place to the north east of the city, in the quarter circle stretching from Upper Northgate Street to Foregate Street. A whole new housing area, known as "New Town", grew up to the north of the Chester Canal, in the vicinity of St. Anne's Street and the streets leading off it. At the same time, the land between the canal and Foregate Street and out to Boughton was quickly filled in. Here, in streets like Canal Side, Steam Mill Street, Russell Street, Seaville Street and Steven Street, small terraced houses for the working classes were erected in cheap brick, in imitation Georgian style, with two bedrooms, no garden, a back-yard, and outside lavatory.1 The map, which is based on the official Census of 1841, shows that it was in these areas of greatest expansion that Catholics were congregating. It seems true, therefore, to say that part, at least, of the growth in the north-east of the city was caused by the growth of the Catholic population.

The explanation of this enormous growth of the Catholics is not far to seek. It is possible to trace a few of the older Catholic families over the last years of the eighteenth century into the nineteenth, as will be shown later, but Catholicism in Chester grew so rapidly in the early nineteenth century through the influx of Irish immigrants.

The story of the mass emigration from Ireland, especially during the years of the "Great Hunger" in the 1840's, when the population of Ireland decreased from eight million to four million, has been told more than once. These pages attempt to relate that part of the story which affected Catholicism in Chester. It has several strands, some older than the nineteenth century.

Irish names appear among the recusants in Chester in the early eighteenth century. In 1706, there was a periwig maker, named Philip Doyle, living in Eastgate Ward with his wife, a son named William, and five daughters. There was also a gingerbread maker named Patrick Fitzgerald, who lived in St. John's Ward with Martha, his wife, Richard his son, and a daughter named Katherine.

As a port trading with Ireland, Chester attracted Irish merchants, who came to settle in the eighteenth century. One such person was the Francis O'Brien already mentioned, who must have immigrated into the city about the year 1760, and subsequently married a member of the Anglican Church. The majority of the Irish people mentioned on the Papists' Returns of 1767, however, were poor labourers and domestic servants, like Roger McGinnis, a gardener, John and William Murphy, probably brothers, who were described simply as "labourers", and Sarah Hynes, a servant.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the poor from the Irish countryside were beginning to appear in Chester in much larger numbers. During the next fifty years, they came in two great waves, as famine and disease struck their own land. The first large-scale settlement began in the last decade of the century, after a severe outbreak of famine, and the distress which followed in the wake of the rebellion of 1798. The agricultural depression which set in after the Napoleonic Wars drove yet more out of Ireland. In 1821, the Irish potato crop failed, and the consequent famine and disease, which were almost as bad as in 1846, led to a wholesale movement into the growing industries in North West England, and expanding canals and railroads. The coming to Chester of large numbers coincides with the great rise in the population which was already mentioned. Some came via Liverpool and Holyhead, but for many the journey was made possible by the development of regular steam packets to Chester, in which the fares were low and the boats recklessly overcrowded. Many of the immigrants were from the less prosperous counties of the south and west, like Mayo, Roscommon, Galway and Clare. This is shown in the first marriage register of the Catholic chapel of Chester. For instance, John Gallacher and Mary Brogan, who were married in 1833, both came from County Mayo. In 1834, three out of the six couples that were married came from Ireland. John Walsh from Fermety, Roscommon, and Margaret Tobin from Cullin, Tipperary were among them.

The majority must have found homes for themselves in the poorer working class streets in the north east of the city. At a time of rapid expansion, they provided a pool of cheap labour. Some found work in the tanning works on the north side of Foregate Street, others were absorbed into the rope-making works adjacent to the north and west walls of the city. There was a considerable amount of road-making going on in Chester at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In 1801, Northgate Street was widened, and in 1827-29, Grosvenor Street was cut through a densely populated area from Bridge Street to the River Dee, and a new bridge was constructed across the river. Irishmen were employed in the heavy labour this kind of work involved, in the same way as they were as "navvies" in a later decade, for the construction of the railways. The low wages they were prepared to accept could lead to bad feeling and hostility from local labourers, which occasionally erupted into violence. In 1835, there was an affray in the city when a party of Irish road-makers were attacked by Chester labourers, and two of them were beaten and abused. The affair was reported by the Clerk of the Peace for Cheshire, Mr. Potts, and used as evidence in the Government Report on the State of the Irish Poor in Great Britain, published that year.2

There were similar incidents in the 1830's, both in the countryside outside Chester when Irish agricultural labourers hired themselves out at harvest time, and also during the construction of the Chester to Birkenhead Railway, when troops had to be brought out from Chester to break up a pitched battle. It is not very likely, however, that Chester people were involved in any of these incidents. Harvesting was usually carried out by seasonal migrant workers, and navvies moved on as they constructed sections of railway lines.

Even casual labouring jobs gave the Irish better wages and security than they had enjoyed at home. Some took up petty trading like hawking and huckstering; others kept beerhouses and lodging houses, where shelter was given to fellow Irish less fortunate than themselves.

In the story of the Irish in Britain, it is perhaps the dramatic which has been emphasised. In a town like Chester, where conditions were never as bad as those in a great city like Liverpool or London, it must have been the day to day experiences of ordinary families accustomed to a rural life, as they tried to adjust themselves to an entirely different environment and way of life, together with the loneliness of exile and the social difficulties, which caused the suffering and distress. Such things can go unnoticed or forgotten. They lay at the basis of the appeal drawn up by the Cheshire priests, led by John Briggs in 1826, which speaks of "the many Irish (who) by great distress have been driven from their homes, and have settled among us; who through centuries of severe sufferings have preserved the precious treasures of their faith".3

The official Census of 1841 recorded the presence in Chester of 1,013 Irish immigrant men and women. This figure multiplied as the third great wave poured in during the Famine years, and reached its crest in 1851. Many of the new arrivals came as complete family units, father, mother, one or more children and sometimes a grand-parent. Others, though less numerous, came as single young men in their twenties and thirties. Most sought out relatives and friends, in their search for employment and accommodation. They tended, therefore, to congregate together, often sharing already overcrowded houses in the poorest quarters of the city. The highest concentration in numbers was in the Steven Street area, by now a traditionally Irish quarter, and in Boughton, left vacant by the gentry as the Leadworks moved in.

Enormous economic problems were created for the city by this great influx. The Chester Courant of 15th January, 1847, publishing an appeal for the poor, spoke of the high price of provisions, and the distress of the Irish. It listed the number of Irish in each street, and those in great distress. There were four hundred and sixty nine in Steven Street alone, and of these, one hundred and twenty nine were in great distress. Canal Side, though it had a smaller number (sixty five), was in a worse plight, with fifty nine in distress. Of the one hundred and fifty one in Boughton, nearly half, (sixty seven) needed urgent help, as did Steam Mill Street with forty nine out of seventy one in distress. The newspaper wrote of "Unfortunate and starving creatures, huddled up in large numbers in very confined and filthy dwellings".

The city authorities were not able to keep pace with the rising tide, and new housing lagged behind. Courtyard dwellings, with their typical lack of proper ventilation and sanitation, developed in the entries behind the shops of the main streets, and here also many Catholics could be found. Some of the larger houses, once the town houses of the gentry, were subdivided as tenements for families. One such example was the Victoria Buildings in Lower Bridge Street.

Many of the men who came over in the Famine years, especially those in Steven Street and Canal Side, gave as their occupation for the 1851 Census, "Agricultural Labourer", which must have been the work they were doing in Ireland. They found work now on the land, in the nurseries and market gardens south and west of the river, where a large number of "hands" were employed. Others simply called themselves "labourer", and this covered a wide range of occupations. Some were employed by the Railway in unskilled jobs, as goods and coal porters; one was a Railway watchman. Others worked in the lead works, in brewing or milling, or as brick setters' and bricklayers' labourers. In many cases, grown up daughters found employment in domestic service, or as dress makers, milliners, seamstresses and cap makers.

The priests bore the heavy responsibility of the spiritual welfare of the immigrants. Sheer numbers, nominal Catholicism at least for some, migration in and out of the city must have made it difficult to get to know all of them. At times, it must have seemed a superhuman, heart-breaking task. Yet it was undertaken, in spite of the cost. At the same time, many turned to the priest for help and advice of every kind. Father Briggs, we have seen, looked after their money for them, sent it home when they asked, and if they died, disposed of it as they requested. The notes he scribbled in pencil also show that he was often writing their letters for them. One such note is a reminder to write to William Casey, a first year student of Divinity at Maynooth, telling him that William Magennis wished him to come over to Chester during the vacation. Another time, a sailor named Archibald McAlister wrote to him, asking him to let his wife know that he was about to board ship. It was written from the dockyard at Chatham, but the letter adds that he does not know where they are sailing to.

Father Carbery witnessed the distress of the 1840's, and the hardship of the severe winter of 1860-1. At Christmas 1860, the Committee for the Poor Relief Fund of Chester set up a soup kitchen in Duke Street, at which the soup was sold at 1d. a quart. By January 12th, 1861, seven hundred quarts were being sold daily. The Chester Chronicle not only praised the Committee for the work it was doing, but also the "dissenting clergy" for the hundred tons of coal they had distributed. The Catholic priests were surely among them!

Throughout the nineteenth century, a hard winter could throw many men out of work, especially when they were engaged in casual labour. This is reflected time and time again in the school log books, when parents are too poor to supply their children with copy books and slates, or children are absent from school because they have gone to the soup kitchen. As late as December 1880, a hundred of the poorer children were given tickets, entitling them to a free dinner at the Town Hall, from "Miss Jones's Charity". A month later, between fifty and sixty pairs of clogs were given to the poorer boys by the School Attendance Committee, a gift which had to be repeated more than once.

One of the most difficult problems which the Catholic Church in England had to face in the nineteenth century was the fusion of its English and Irish members into one united body - the Body of Christ. On the one hand, English Catholics saw their hard-won liberty jeopardised, as they thought, by the crowds of immigrants who flocked into their towns. On the other hand, Irish Catholics often equated their nationalism with their faith. Yet, without them, the Church could hardly have expanded and developed. That the task was accomplished in Chester was due in large measure to the priests who worked in their midst, particularly the forthright Lancashire man, John Briggs, and the kindly and respected Irishman, Edward Carbery.

| The Building of St. Francis's | Contents | CHAPTER IV: Some Catholic Families of the Nineteenth Century |

From Catholicism in Chester: A Double Centenary 1875-1975 |

||

| © 1975 Sister Mary Winefride Sturman, OSU | ||