St Werburgh's Roman Catholic Parish, Chester

Catholicism in Chester

Chapter VI: Parish Life in the last hundred years

Visit to St. Werburgh's of King Alfonso XIII of Spain, 1907. Visit to St. Werburgh's of King Alfonso XIII of Spain, 1907. |

The final chapter of this story attempts to reconstruct Catholic life in Chester during the last hundred years. One of its most striking features is the steady increase in the Catholic population. The other is the vigour and expansion of the life of the Church, in spite of the great poverty of the majority of its people.

On one occasion in 1889, Father Lynch said that his congregation numbered 2,000. By 1907, he had seen it increase to 2,600, and by 1929, it numbered 3,500. At the same time, St. Francis's parish grew from 800 to 1,300. Catholics by that date numbered about one in ten, in a total population in the city of about 40,000. In spite of a certain drop in numbers during the two World Wars, by 1951 St. Werburgh's had 4,600 members and St. Francis's 2,400.

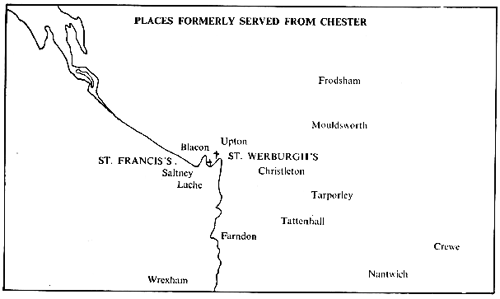

While it had long since ceased to be necessary for the priests to serve distant centres like Crewe, Nantwich or Wrexham, which now had their own churches, the increase in population and growth of new suburbs in and around Chester itself brought about the opening of new Mass centres, dependent on the mother-churches of St. Werburgh's and St. Francis's. In November, 1906, Mass was said for the first time at Tarporley by Canon Chambers of St. Werburgh's, for the benefit of the small Catholic population, which had been increased by the arrival of twenty Irish workers. At first, a room, used as a cheese-loft, was lent in his house in High Street, by a Mr. Martin Goulding, and here Mass was said once a month. In 1937, the Salvatorians took over the Mission, and in 1941 a small church was built. In more modern times, a similar growth has taken place at Mouldsworth, TattenhaII and Farndon, and in particular at Upton-by-Chester. Here, a flourishing Mass centre was opened in 1939, which has subsequently become the parish of St. Columba's, with its church built by the present parish priest of St. Werburgh's [Canon Murphy]. In addition, the coming to Christleton Hall of the Society of the Divine Saviour in 1934 gave a new chapel to the parish, as well as another Religious Order. Regrettably, the Salvatorians have since had to leave Chester.

In the meanwhile, the work of the Franciscans at the other end of the city led to development on the other side of the River Dee. Saltney has already been mentioned. St. Clare's, in the Lache, was opened in 1960. The entirely new parish of Blacon, in the care of the secular clergy, was begun in 1956, and its church of St. Theresa's opened in 1959. Thus, it can be said that from the tiny room in Parry's Entry, five flourishing parishes in Chester alone have been developed, as well as several other Mass centres.

When Canon Buquet left for Birkenhead in 1882, he was replaced for a year by Canon Dallow, and then in 1883, by Father Edward Lynch. Father Lynch was a Londoner by birth, educated at Sedgeley Park School in Staffordshire and at Ushaw. After his ordination in 1869, he became curate successively at Chester, Shrewsbury, Birkenhead and Seacombe, before finally returning to St. Werburgh's as parish priest. He continued to hold this position for the next twenty years.

Father Lynch found himself faced with the enormous debt, for those days, of £7,000, and throughout the years he struggled constantly to reduce it, so much so that it eventually told on his physical strength. His own people, who were poor and often in acute distress, did what they could to help reduce it. Towards school expenses, the children were asked to bring, "a pingin (a penny) to the sagart (the priest) every week". There was a weekly outdoor collection to reduce the debt on the Mission, and this realised about £2 a week. The Easter collection for the three priests came one year to £4 4s. i.e. £1 8s. 2d. each. All sorts of other money-raising devices had to be found, to pay off the debts, on the church until Canon Tatlock's legacy wiped them out, and on the schools. Concerts, charity sermons, and lectures were common favourites. Seat rents, undesirable as they might be, were levied for certain pews in the church, as another way of finding money. One notice in the Parish Notice Book, before Canon Lynch's time, it is true, gives us an idea of the desperate straits priests could be in, where money was concerned. It reads:

The attention of the congregation is called to the charges made in this church for entrance to the floor and to the gallery. At the first Mass, 1d. for each person in any part of the church. At the second Mass, 2d., at the third 2d. for the greater portion of the church. Under the gallery, payment is left to the option of those who go there. Last week from a well-filled gallery 4/6 was collected, and 1/3 for the offertory.

In 1890, a Grand Draw was held with special prizes to tempt people to purchase tickets. It was a year of severe unemployment in Chester, followed by great cold, but Canon Lynch struggled to raise £200 from the Draw, in order to reduce the debt by another £1,000. Helped by kind friends, he managed to obtain £240, and in thanking those who had contributed, he said that the smallest donation would be gratefully received. What was accomplished by the Catholic population in those days of hardship is amazing. Not only did they help to support their priests, church and schools, but other calls of all kinds were made on their generosity. There was always an annual collection to help the Chester Infirmary, and the congregation was asked to be generous, "because of the help it gave to the sick poor". There were a number of other appeals, which seem never to have been turned down, even though they must have eaten into the small wage packets of the givers. Among them can be listed the Holy Land, a famine in India, African slaves, the building of Westminster Cathedral and the opening of a new church of St. Patrick in Rome. At the same time, the parish priest was appealing for the distressed poor of the parish.

In 1886, Father Lynch stood for election for the Chester Board of Guardians. He urged his parishioners not to stand aloof from these elections, because to him they were a way of protecting the Catholic poor. He and the schoolteachers were continually telling Catholic parents who could not afford the school-fee for their children, to seek assistance from the Board of Guardians. There was obviously an unwillingness to do this, probably because the organisation was associated in their minds with the idea of the Workhouse. That this dreaded place was not unknown to poverty-stricken Catholics is clear from entries in the Parish Notice Book and the School Log Book. In 1886, the congregation was told that when a Catholic child was sent to the Workhouse, its friends should see that its name was entered on the workhouse books as a Catholic, and call the attention of the priest to it at once. Through not doing this, Father Lynch told them that hundreds of children were being lost to the Church. Whether the "hundreds" refers to Chester or not is not clear, but in any case it is an indication of the poverty of the time before the Diocesan Rescue Society was established in 1889. There is one pathetic entry in the Log Book of the Boys' School in 1881, which recounts the fate of two boys, William and John Looney. They had lost both their parents within a fortnight of each other. As a result, the boys were obliged to leave St. Werburgh's school and go into the workhouse. Not long after, the schoolmaster entered in his Log Book the sum of 7s. 8d. received from the Board of Guardians for the fees of pauper children.

The surviving parish records throw some light on the religious tone and practices of a hundred years ago. The sermon clearly played an important part in Sunday observance, whether it was Mass or the evening service. As far back as the time of Thomas Penswick and John Briggs, the sermons they preached were long remembered, and even found their way into print. Unfortunately, none have survived, nor has a translation from the French by Thomas Penswick, entitled "The Love of Jesus in the Adorable Sacrament of the Altar". Throughout the nineteenth century, Jesuits were most frequently in demand, Father Tarleton from Liverpool, Father Caldwell, Father Hassan. Occasionally, the subject of their sermon is also recorded. "Nuns" was the subject chosen by Father Edgecombe when he once preached on the patronal feast of St. Werburgh, always a day of great solemnity in the parish. On another occasion, Father John Rickaby's acceptance of an invitation was announced, and though the subject of his sermon was not given, it was explained that he was the Professor of Philosophy at Stonyhurst College. Jesuits were also invited to give fortnightly Missions during Lent. In 1889, Father Jackson and Father King came together, choosing among other subjects, "The Love of God", "Drunkenness" and "St. Patrick", in their endeavours to touch every heart. Times of Visitation by the Bishop were also occasions for sermons; and the Visitation records usually specify the subject which the priest wishes the Bishop to speak about, "God in our lives", or "The more frequent reception of the Sacraments", or "Indifference".

In addition to the weekly, and no doubt, lengthy sermon, music, both vocal and instrumental, seems to have played an important part in religious worship. In Father Carbery's time, there was a "good organ". An undated letter to Father John Briggs has survived which shows how very earnestly the choir carried out its functions. It is signed, "R. Gorst, Junior, J. Tatlock, John Barker". It complains about the wretched state of the choir, through "the want of strength and skill in the Treble part". It puts the blame for this squarely on Father Brigg's shoulders - though one would have thought he already had more than enough to cope with - because, as the letter reads, "You have often mentioned it, but not attempted to remedy it". Who the offending Treble was is not stated, but the priest might have risked offending someone he could not afford to. In any case, the letter continues,

We, the Contra-Tenor and Bass are mortified by our endeavours being spoilt by the unskilful performance of the Treble, and by the unharmonious discordance. Until a remedy is found, our services will be withheld.

That the choir sang every Sunday appears from the next part of the letter, for it goes on:

We shall desist from singing for the next few Sundays, and you must make observations from the pulpit. If the congregation does not help, we shall give up the choir.

What happened as a result of this ultimatum does not appear. A church choir certainly existed in 1867, for the parish notices that November announced a concert in its aid, adding that it "deserves the hearty support of the congregation".

One of the most important ways of promoting parochial life in the nineteenth century was the formation of confraternities, sodalities and guilds of various kinds. In a letter to the Bishop, Father Carbery mentioned that there were two confraternities in the parish, though he did not specify what they were. Twenty years later, there were four, the Catholic Young Men's Society, the Children of Mary with its subsidiary Congregation of the Angels for younger girls, the Christian Mothers' Guild and the Altar Society. In addition, there were four other organisations, which in the days before the Welfare State, acted as mutual benefit societies. One was called St. Patrick's Burial Society, another, St. Anne's Catholic Burial Society, the third, the Wirral Catholic Benevolent Society, and the fourth, the Catholic Tontine Society. The aim of the confraternities was to promote the spiritual growth of their members by prayer together, and by regular reception of the Sacraments, especially the monthly Communion day. In addition, they formed valuable auxiliaries for the clergy, helping them in the weekly outdoor collections, and organising the various parish activities, especially those connected with money-raising projects like concerts. It is probably true to say that the stronger and more flourishing the sodalities were, the more closely integrated was the life of the parish. Their contribution to its growth was, therefore, an important one.

The Catholic Young Men's Society must have been founded in Chester towards the end of 1864. It had already existed several years in the north of England, where it was particularly flourishing. The Chester Courant devoted a paragraph of its number for November 23, 1864, to the second soirée, as it called the meeting, held in the schoolrooms in Queen Street. Father Hopkins presided over the tea-party and concert, at which two hundred were present. From that time onwards, the society steadily progressed, and the pattern of meeting inaugurated in 1864 continued for many years. There are frequent references in the Parish Notice Book to "the usual literary entertainment" - given on one occasion by "The Emerald Ministrels" - or a lecture, or again a soirée. Many of the concerts in the parish were organised and also executed by the Young Men's Society, as a number of surviving bills advertising them show. These have all the flavour of the typical nineteenth century entertainment, in the days before radio and television; the solo songs, the piano duets, the Victorian poetry, all are there. On more than one occasion, preparations for the concert caused no little disturbance in the schoolroom. Once, the erection of a stage at the end of the classroom for some entertainment, possibly "The Emerald Ministrels", whoever they were, prevented Luke Ryder from giving the monitors their late afternoon lessons.

In addition to the Young Men's Society and the Children of Mary, St. Francis's parish naturally had the Tertiaries or Third Order. One other organisation for children must be mentioned at St. Werburgh's, because it reflects the attempt to combat one of the great social evils of Victorian working class life, namely drunkenness. It was not uncommon, especially in the great industrial towns, to find a startling mortality rate among children brought about through this, and in 1884, Cardinal Manning began the Children's Temperance League of the Cross, to try to safeguard Catholic children. In 1886 the League of the Cross was established in St. Werburgh's parish, and a large number of children took the pledge it required, and joined it. The Band it possessed by 1906 must have caused something like a stir!

The aspirations and needs of modern Catholic life have, naturally, brought into existence their own organisations. The first parish "conference" of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul met at Chester in 1906. To this have since been added the Knights of St. Columba, the Legion of Mary, the Catenians, and the Catholic Women's League.

One gets the impression, reading the parochial records, that much was demanded from Catholics a hundred years ago, that the Church has seen fit to relax in modern times, or perhaps leaves more to the responsibility of the individual. There are, for instance, frequent reminders in the Parish Notice Book, of the regulations about fasting, on the Wednesdays and Fridays of Advent and Lent, on the Ember Days at the four different seasons of the year, on the eve of Christmas and Pentecost and the feast of St. Peter and Paul. In times of severe epidemics, these laws were relaxed by the Bishop. In 1886, a dispensation from abstinence was granted during an outbreak of cholera, and a notice is warning the congregation just before Advent that it will now cease. Similarly, in early 1890, when there was a severe epidemic following a bad winter with much hardship and unemployment, there was no fasting or abstinence throughout Lent, except on Good Friday. Another aspect of Catholic life which has a ring of austerity, as well as throwing light on the working conditions of Victorian times, was the hours of the Masses on Holydays of Obligation. During the 1860's, they were normally at 5 a.m., 7.30 a.m. and, for the school children, at 9 a.m. The earliest Mass was for the benefit of the workers before they set off on their long daily trek to work in such places as Widnes and Ellesmere Port. One old Catholic of Chester, not long dead, used to recount how he left home each morning at 6 o'clock, in order to walk to his work, and had the long trudge back each night, reaching home at 8 o'clock, then to bed in order to be up in time again the next day.

While the Faithful Companions of Jesus were engaged in their educational work in the now flourishing grammar school for girls at Dee House and in their equally important teaching in St. Werburgh's schools, the parish was able to welcome another Religious Congregation into its midst in 1911. This was the Little Sisters of the Assumption, who did such wonderful work especially among the sick poor, during the years they remained in the city. They came to Chester through the instrumentality of Miss Josephine Hall, to replace the Catholic District Nurses for whom she had been responsible. At first, they lived at 45 Queen Street, and from there they visited the sick in their own homes. Later, they opened a dispensary at 34 Queen Street, in addition to their other work. In 1913, they were given the land for a proper convent and chapel in Union Street by Miss Margaret Collins, the sister of Patrick Collins, the founder of the popular Collins Amusement Fair, whose family were great benefactors to the Church.

The story of the career of Patrick Collins has a Dick Whittington quality about it. "Pat" was the second son of an Irish Catholic, John Collins, and was born, possibly in Steven Street, in 1859. His father was a showman, who travelled about Cheshire, North Staffordshire and Lancashire with his hand-turned roundabout. Patrick grew up on the showground, helping his father not only with the roundabout, but also defending the pitches where they stopped, against the gangsters who attacked them. By the time he was twenty one, he was married to Flora Ross of Wrexham, and possessed his own horse and roundabout. Before long, he was touring the Midlands in the caravan which was his home, launched on the career which was to win him the title of "King of the Showmen". The roundabout grew into "Pat Collins's Amusement Fair", full of lights and noise and excitement, which was eagerly awaited all over the country. Sutton Coldfield, Barry Island, Colwyn Bay, Yarmouth, all had pleasure grounds which he purchased. He travelled everywhere, including the continent, buying the "Big Dipper", the switchback, the traction engines and the caravans which attracted crowds to his fairs.

Fame and money never made Pat forget his humble origins, or the poor and sick. He believed that he had made his money through the people and that it must go back to the people, and his favourite saying was, "We only pass this way once; let us do what we can, when we can". Whole days' takings on the fairground were frequently handed over to good causes. The Fair's appearance on the Roodee each year meant money for the Royal Infirmary. Nor was the Church forgotten. The pulpit in St. Werburgh's, among others, was his gift. His generosity was continued by his second wife, Clara Mullett, whom he married in 1935.

From 1918 until the time of his death, he was a member of the Town Council of Walsall. He was made an alderman of the Borough of Walsall in 1930, and became Mayor and a Freeman of that city in 1939, when he was eighty one years of age. From 1922 to 1924, he sat in Parliament as Liberal M.P. for Walsall. He died on December 8th, 1943, leaving behind the memory of a greathearted man, who by innumerable acts of kindness and generosity had helped the poor, the sick and the suffering.

During the First World War, when wounded Belgian soldiers were brought to Chester, the Little Sisters turned their convent into a small hospital in order to help in nursing them. In recognition of their charity, the King of the Belgians awarded the Superior with the Medeille de la Reine Elizabeth. A Belgian priest, Father Loos, joined the presbytery during these years and gave the men much spiritual help, before he himself was called up as an army chaplain. As the War progressed, many Catholics went out among the Chester men, to fight at the "Front". The Parish Magazine recorded regularly the names of those wounded or killed in action.

As one of the larger and more important churches of the diocese, St. Werburgh's has been used more than once for important functions. As recently as February 1948, the Most Reverend John A. Murphy, now Archbishop of Cardiff, was consecrated here Coadjutor Bishop of Shrewsbury. The church has been used twice for ordinations. In August, 1886, two priests, Father Hennelly and Father O'Grady, were raised to the priesthood, and for the occasion, Canon Lynch appealed to his congregation for money to help him to purchase a new carpet for the sanctuary. On the following Sunday, Father Hennelly sang his first High Mass in the church. These two priests do not seem to have been directly connected with Chester, though Father Hennelly may have been related to Patrick Hennelly, for whom the congregation was asked to pray the following year, when he was dangerously ill, and who died soon afterwards. Another ordination took place in 1905 which is of particular interest, because it appears to be the only one of a Chester boy, Andrew McGeever, though there are references among Father Brigg's papers to his arranging to send boys to Lisbon to prepare for the priesthood. Andrew McGeever must have been born about 1880, since his name appears in 1894 as one of the two boys in Standard VII of St. Werburgh's school, when he would have been about fourteen years of age. He was then living at 4, Hoole Lane, and by then his father was a coal merchant. The Census Returns for 1871, however, enter particulars about two families of McGeever living that year in Steven Street. John McGeever, then aged 36, was probably Andrew's father, and John's brother, Andrew, then 30 years of age, may have been the uncle after whom he was named. Both, together with their wives, had been born in Ireland, as had another brother, Thomas, living with John's family. The only son John then had was Hugh, a baby of one year, and he also later became a priest. Both John and Andrew classified themselves for the Census as "labourer in the oil works", probably at Ellesmere Port, so that John must have prospered as a coal merchant in his later life. Unfortunately, the Parish Notice Book for 1905 is missing, and the Parish Magazine while making much of the fact that he was a Chester boy, gives no other details about Andrew. Possibly, other records, had they survived, would have told us more about his brother. Andrew McGeever died, a comparatively young priest of 42, in the January of 1922, whereas Hugh lived on until 1934, as Canon and the parish priest of Our Lady and the Apostles, Stockport.

An occasion very different from the ordination of a priest was the visit to St. Werburgh's of King Alfonso XIII of Spain in the December of 1907. The Chester newspapers, especially the Courant, describe this with vivid detail. The king, then a young man only twenty one years of age, and recently married to Princess Ena, was paying a private visit to the home of the Duke and Duchess of Westminster, Eaton Park. He was accompanied by three Spanish Lords, including the Duke of Alba, a future ambassador to England. On the Sunday, all of them drove through the city to St. Werburgh's, to assist at the 11 o'clock Mass. Crowds gathered in Grosvenor Park Road, to see and cheer them, and the red carpet was rolled out for them, from their carriage to the church door. They were received by Canon Chambers and Father Hayes, accompanied by cross-bearer and acolytes. The King was led in procession through the packed church, to a special seat in the sanctuary, on the right of the altar. The writer of the article in the Chester Courant remarked on the contrast in the worldly condition of the worshippers at the Mass, "the monarch and the sons of the highest nobility of sunny Spain, together with the blue-jersied peasantry, the Italian women and the Boughton women wrapped in shawls, all worshipping under the same roof". A Low Mass was celebrated by Canon Chambers, and afterwards the royal party left the church to the strains of the Spanish National Anthem. The king, on whom the shadow of abdication and the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War had not yet fallen, remarked that his cordial reception in Chester was like being back in Spain. The parish magazine gratefully recorded the £5 left for the church building fund.

If the visit of a reigning monarch was regarded at St. Werburgh's as the high light of the year 1905, the visit of the Papal Legate was an even more auspicious occasion. This took place in July, 1932. Here again the parish magazine was outdone in its description of the event by the newspapers, which this time carried photographs as well as long articles. Such was the position now held by the Catholic community in Chester. The Eucharistic Congress was taking place in Dublin, and Cardinal Lorenzo Lauri, on his way there from Italy as the Papal representative, broke his journey in Chester. He travelled from London by a special royal coach, in the company of five clerical students and Mgr. Walsh from Dublin. The Chester Chronicle speaks of "the scenes of unparalleled religious fervour" of hundreds of Catholics who assembled outside the General Station to catch sight of the Pope's representative. The clergy of all the surrounding churches welcomed him, Father Hayes as the parish priest of St. Werburgh's accompanied by his curates, Father Murphy and Father McGinley, and Father Stanislaus from St. Francis's, together with the priests from Connah's Quay, Saltney, Ellesmere Port, Talacre and Neston. The Catholic Young Men's Society, wearing their sashes, formed a guard of honour. The crowds cheered and knelt for his blessing, as the white-haired, kindly and smiling cardinal passed through their midst into the Queen Hotel. It was the first time for 1,500 years that a Papal Legate had stayed in Chester, and the Catholic crowds were clearly moved. Before long, the area round the hotel was resounding to the singing of "Faith of our Fathers".

The following morning, the cardinal went to say the seven o'clock Mass at St. Werburgh's, which was beautifully decorated for the occasion. The response of his people to the Papal Legate's visit must have pleased Father Hayes, for the church was crowded, and five hundred received Holy Communion at the cardinal's hands, while one of the papal suite told him, "It is one of the most beautiful churches I have ever been in". After the cardinal's departure, Father Hayes spoke of the courtesy and kindness of all the railway officials of the General Station, of the staff of the Queen Hotel and of the press. This, together with the ways in which Catholics had shown their loyalty - in their flag-bedecked homes and their kneeling crowds - illustrates the strides Catholicism had taken in Chester over the years. The Catholics of Chester might still be poor, but they were no longer the tiny handful of unknown and unwanted recusants living in the courts and entries of the city, and attending Mass in an upstairs room in Parry's Entry. The Church had reached its maturity, and its members were ready now to come forward and play their full part in the life and government of their city. The Cestrians, too, were prepared to accept them as fellow-citizens on a par with themselves, and as good neighbours.

The double celebration of the centenary of St. Werburgh's and St. Francis's parishes stands out as a landmark in the history of Catholicism in Chester. In many ways, it closes a chapter in that history, one of struggle against great odds, out of which the Church has emerged, purified and strengthened by the ordeal. As she moves into a new era of her existence and faces different challenges and demands, she may not forget the past out of which she has grown, the recusants who languished in Chester Castle for their beliefs, the faithful remnant who persevered throughout penal times, and the poverty-stricken exiles on whose pennies her churches and schools were built. These pages have been written to help her to remember!

| Chapter V: Catholic Education in Chester | Contents | Notes on the chapters |

From Catholicism in Chester: A Double Centenary 1875-1975 |

||

| © 1975 Sister Mary Winefride Sturman, OSU | ||